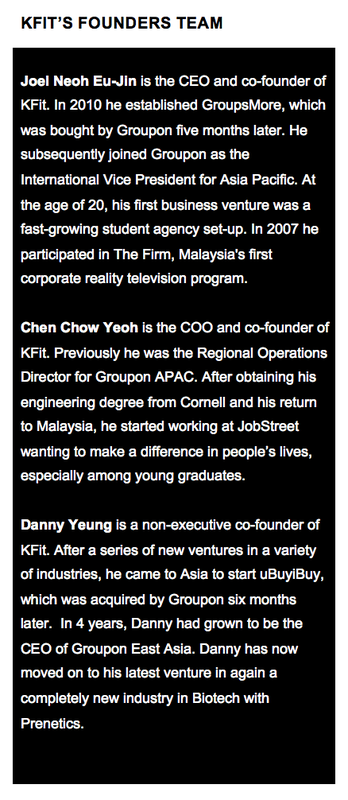

| What do Taxi Meters and Fitness Club Memberships have in common? Nothing much at first glance. But most likely both of them are destined to join Photographic Film in the Permanent Exhibition of Business Relics at the Museum of Disrupted Industries. Taximeters are demoted into antiques by the rideshare apps, like Uber, Grab(car), and Didi Chuxing (formerly Didi Kuaidi), who successfully disrupted the taxi business. Their conquest is now turning into a throat-cutting Ride Wars. But what makes the Ride Wars truly fascinating is that the apps revolutionized a traditional inefficient industry into a community-based platform business that centers on optimally and timely matching both drivers and riders. Similarly, rising from Kuala Lumpur (KL), a new young platform business is determined to fulfill its mission of creating healthy network effects in Asia: KFit (‘Keep Fit’) offers subscribers cheap, convenient health and wellness options. The 1-year-old born global from Malaysia is regarded as one startup from Asia to watch closely. The company raised over US$15 million in less than a year and is backed by high-profile investors Sequoia Capital and 500 Startups, among others. It has also broadened the scope of its business: it started out simply offering unlimited gym classes – akin to US-based Classpass – but now covers massage services, spas, and salons as well (TechCrunch, 2016). How It Started It was early morning 6 a.m., in March 2015, when Chen Chow Yeoh received a phone call from his business partner, serial entrepreneur Joel Neoh. Joel was calling from a ski-resort in Japan, where he was spending his winter holidays. He and Danny Yeung, former CEO of Groupon Hong Kong, currently CEO of Prenetics and a personal friend, had been talking through the previous night about an extremely exciting new business opportunity. The opportunity excited him, as the ‘Uber of the Fitness Market’ could well disrupt the whole traditional gym industry. “Hardly 4% of the population has a gym membership.” In his analysis of more and more health-conscience societies, the fitness membership still gives consumers a lot of headaches: generally these are seen as expensive, inflexible and too much locked-in, and a poor user experience, which was also unsociable for many people. “While 40% of customers like going to the gym with their friends” (Video Wilddigital, September 2016). Furthermore, perhaps as a consequence of failing to offer what most people desire, the fitness clubs themselves operated suboptimally; often with dramatically low occupancy rates, some lower than 10%. Whereas service industries like hotels and airlines work with averages of 80+%. To fight the low occupancy rates, excess capacity, and customer churn, the clubs are accustomed to compensate by putting a lot of efforts on customer acquisition resulting in high CAC (customer acquisition costs). Joel: “For a consumer to get into a gym, you had to subscribe for a year. At the same time the Classpass model was doing very well [in the US], it had just raised US$40 million and I thought it would work here” (Tech in Asia, 2015) In their discussions it had become clear to both Joel and Danny that to make this concept a success, it required a quick international rollout and smooth operations. Almost immediately upon Joel’s return to Malaysia, he and Chen Chow started their next entrepreneurial venture. KFit (from ‘Keep Fit’) was created as a platform to connect users to fitness studios, classes and gyms. In order to quickly claim key cities across the Asia-Pacific, the duo successfully raised seven-figures, in US dollars, in a seed-funding round from both 500 Startups and SXE Ventures. Two angel investors also joined in — Daniel Shin, founder and CEO of Ticket Monster and Danny Yeung. The team believed fitness to be largely an untapped category in Asia and the challenge of building something greatly appealed to them. | Rapid International Expansion Within the short time span of six months, KFit employed over 100 people as it expanded operations into eight Asia-Pacific (APAC) markets. The first launch of the App was mid-April in KL, the company’s home market. Then, a few weeks later, KFit stepped into the international markets of Singapore in early May; Melbourne in mid-May; and, Hong Kong in late May. This was followed by Sydney in June; Taipei and Auckland in July; Perth and Manila in August; and finally, Seoul in September. The KFit organization is built around a hub-spoke model, with the hub in KL hosting the core leadership group with eight functional teams (Technical Development, Data Science, Customer Service, Partner Management, CRM and Regional Marketing based in KL, along with other supporting functions like HR and Finance). The spokes with teams for Business Development teams, Corporate Sales and Local Marketing are located in the local country markets and focused on the acquisition of gyms. Of all of these KFit employees, about 30% work as sales reps, knocking on gym doors in order to sign them on to the App. The pace at which markets were entered was determined primarily by the hires that the two co-founders were able to recruit. During the team’s hyper-growth phase, Chen Chow explained: “It is all about hire fast and fire even faster. We can’t afford to slow down. Our business strategy requires new hires that can keep up with our speed of doing business.” Typically, Joel and Chen Chow would go into a new market for about five days, having already set up interviews for up to six people per day. This way they would manage to clear 30 candidates relatively quickly. Subsequently, they would make suitable candidates offers and ask the ones hired for key positions to join them in KL to work for three days with the core team. This provided them with the necessary insight as to whether there was a good fit between the candidate and the team’s fast-paced decision-making methods. As testing and tweaking became a major part of KFit’s business approach, in order to adapt quickly to new and different markets, Chen Chow stimulates his people to conduct focus groups and perform small experiments. He wants them to be able to convince him with data-based evidence before they could successfully scale up: “Because I look at the numbers, all my evaluations are metrics-based. What’s important to realize is that major improvements can already be achieved with seemingly small steps. For instance, just an increase in the number of daily visits by our sales reps from an average of four, to six per day, which we think is a good number, translates to an increase of 25-50%. On the scale of the whole team, that is impressive.” Each day the KFit management receives reports on 150 variables, focusing primarily on a set of 15 key metrics. The weekly business review with all of the country managers begins with a review of these metrics, rather than an activities debriefing. Daily growth meetings are with the local teams, where radical ideas for “nearly zero-budget” guerilla marketing tactics are rewarded, such as a KFit fitness instructors wearing black KFit t-shirts planning to ‘photobomb’ the public appearances of celebrities or well-known politicians during events where fitness exercises are demonstrated. Another low-cost tactic example was local KFit teams joining the popular five-kilometer Color Run races. The teams were running with large Smart-phones on their backs advertising the KFit app. |

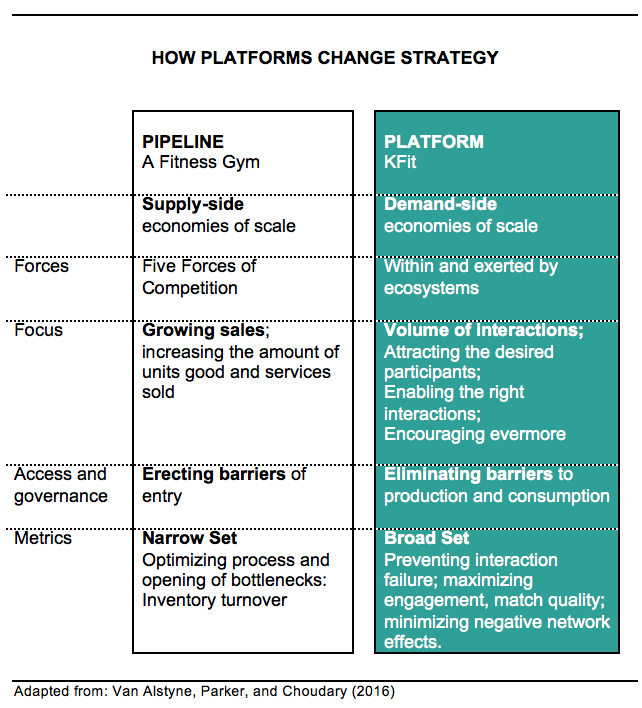

| Analysis: Pipeline versus Platform Much of the initial success and promise of KFit lies in engineering their business model into a Platform. And not into a Pipeline business, which is the prevailing format for Fitness clubs. Pipeline businesses create value by controlling a linear series of activities—the classic value-chain model. Inputs at one end of the chain (say, materials from suppliers) undergo a series of steps that transform them into an output that’s worth more: the finished product. Clubs create value by owning a gym, having the fitness equipment and employing skilled employees/trainers. They have members that ‘consume’ at the end of the value chain. However, the strengths of the platform-based businesses, as opposed to Pipelines, are fundamentally different. Three Fellows at the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy – Boston University professor Marshall Van Alstyne, Tulane University professor Geoffrey Parker and C-level advisor Sangeet Paul Choudary – identify that the move from Pipeline to Platform involves three key interrelated shifts: | (1) competitive advantage is no longer gained from controlling resources, but by orchestrating the community of resource owners; (2) organizational focus needs to shift from internal organization to external interaction; and finally (3) from a focus on customer value to focus on eco-system value. The MIT-engaged researchers conducted case-based research in order to distinguish four areas where platforms perform differently from pipelines: forces, focus, access and governance and metrics. Their findings are reported in their recent Harvard Business Review article (April 2016), in which they primarily compared Apple and Google versus mobile phone manufacturers, Uber to taxi companies. Here, we will draw a similar comparison but then apply to KFit as a platform business revolutionizing the fitness industry. |

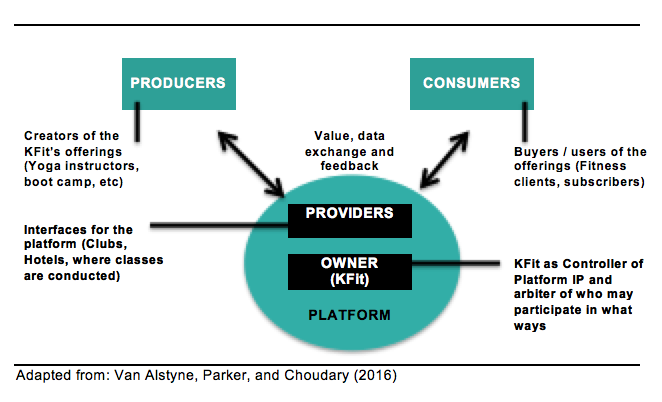

| First off, platforms are not new. They have existed for years: malls link consumers and merchants; newspapers connect subscribers and advertisers. What Van Alstyne et.al. observe is that: “What’s changed in this century is that information technology has profoundly reduced the need to own physical infrastructure and assets. IT makes building and scaling up platforms vastly simpler and cheaper, allows nearly frictionless participation that strengthens network effects, and enhances the ability to capture, analyze, and exchange huge amounts of data that increase the platform’s value to all. You don’t need to look far to see examples of platform businesses, from Uber to Alibaba to Airbnb, whose spectacular growth abruptly upended their industries.” In essence, platforms all have an ecosystem with the same basic structure, comprising four types of actors: owners, providers, producers and consumers. The owners of platforms control their intellectual property and governance; in this case, KFit. KFit also plays a role as an interface provider by having developed the mobile apps and website to serve as the platforms’ interface with users. Equally gyms, clubs and hotel fitness spaces, who make their physical infrastructure available for the gym classes are Providers. Finally, fitness instructors have the role of producers in creating and delivering their offerings to consumers who use those offerings. In creating a platform, KFit had to adopt a different set of new strategic rules in order to compete. First, a platform owner needs to be aware of the competitive dynamics within its ecosystem: platform participants are involved on relatively voluntary basis and may defect if they believe their needs can be met better elsewhere. | As a consequence, KFit as a platform must constantly encourage accretive activity within their ecosystem while monitoring participants’ activity that may prove depletive. If platforms are managed well, it is very easy to move into what were once considered separate industries – like Google has moved from web search into mapping, mobile operating systems, home automation, and driverless cars. Similarly, KFit smoothly expanded its offerings by adding beauty and massage treatments. Secondly, the focus of a platform business is different. While gyms are a pipeline business concentrating on growing sales and class attendance, the fitness platform KFit mainly looks at the value created by the whole community of exercisers/users and fitness providers; therefore its focus is on attracting both sides of the market. Thirdly related to access and governance, platforms relentlessly seek to increase participation by eliminating barriers to production and consumption. KFit encourages the growth of the fitness providers and provides information to improve their class offerings. Gym clubs, however, given by their nature of being a pipeline business, have preference to create entry barriers to others joining their industry. Lastly and fourthly, the set of metrics to monitor the health of their business changes for Platforms too. Traditionally, leaders of pipeline enterprises have long focused on a narrow set of metrics – since pipelines grow by optimizing processes and opening bottlenecks. The inventory turnover is, for them, the metric to watch and manage. Platform businesses in managing their ecosystem take a large set of metrics into consideration: they focus on interaction failures (and fixing them), engagement levels of participants, the quality of the matches being made, and preventing/reducing behaviors which have negative network effects. |

| The ASB Case on KFIT In our eyes, the match of KFit with ASB is an obvious one: both possess the mission and passion to make a lasting impact and aim to be a Platform for Change. Both changemakers have an international outlook from the start, and nurture talent development and a culture for learning, testing and experimenting. Furthermore, the two parties also leverage the powers of combining collaboration and competition. All with healthy network effects. ASB Professors Willem Smit and Ray Fung recently wrote an MBA case on KFit. This teaching case features a critical decision moment in the very early international expansion phase, in September 2015, when KFit got challenged by the US-based competitor ClassPass. The global market leader with international operations in more than 30 cities had just announced the entry into the Australian market – one of KFit’s strongholds. After an unbroken series of victories in the first months, it seemed that the company’s first real competitive challenge had presented itself. What would be best for KFit? What would be an appropriate response to their new international rival? Because, one thing was clear: Australia and New Zealand were an integral part of KFit’s international expansion efforts. , and defending and growing its position over there was key, even though these markets were completely different from other KFit markets, both culturally and economically. This ASB MBA case has been written for learning purposes. In particular, its purpose is to teach about the different types of business models, international marketing and competitive response strategies. If you are interested in obtaining an inspection copy of the case, please write to [email protected] | The MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy Last but not least, the KFit case illustrates very well how MIT’s thinking on the digital economy is put into practice. At the MIT Sloan School of Management, the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy (IDE) consists of a team of visionary, internationally recognized, thought leaders and researchers examining how people and businesses work, interact, and will ultimately prosper in a time of rapid digital transformation. IDE is led by MIT Sloan’s Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, who have co-authored several highly respected publications detailing the interaction of digital technology and employment. These include Race Against the Machine and The Second Machine Age. References Husain, Osman (2016). How Kfit got to where it is today. Tech in Asia. 5:51 AM on Apr 12, 2016. https://www.techinasia.com/story-of-kfit WildDigital (2015). Mobile Revolution – KFit, Joel Neoh. YouTube Video Posted on Sept 25, 2015 - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PBJKhRd0QJk Van Alstyne, Marshall W., Geoffrey G. ParkerSangeet Paul Choudary (2016). Pipelines, Platforms, and the New Rules of Strategy. Harvard Business Review. April 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/04/pipelines-platforms-and-the-new-rules-of-strategy Russell, Jon (2016). Asia-Focused KFit Lands $12 Million To Expand Beyond Fitness Services, TechCrunch. Posted Jan 31, 2016 http://techcrunch.com/2016/01/31/kfit-series-a/ |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed